Oakland Vignette Series: Constrained Choices after the Great Recession

Changing Cities Research Lab

Contributors: Jackelyn Hwang, Vineet Gupta, Alisha Zhao, Becky Liang, and Vasudha Kumar

September 6, 2021

This is the second post in our series of Data Vignettes on Residential Instability in Oakland. Navigate to other posts in this series here.

Our first post on moving discussed how, following the Great Recession, low-SES residents moved less but disproportionately moved out of Oakland and the Bay Area altogether at increasingly high rates. In addition, low-SES residents have increasingly moved to lower-opportunity neighborhoods and households with more adults within the Bay Area during this time period. Altogether, these constraints reflect the increasingly limited options available to lower-SES movers. While we covered moves out of Oakland and the Bay Area in our first post on moving, this post highlights findings from our report on the extent to which Oakland residents have moved into crowded living situations and experienced financial instability since the Recession. Oakland residents moved much less after the Great Recession than before, but lower-socioeconomic status (SES) residents, based on credit scores, made more constrained choices after the Recession. Specifically, they faced tradeoffs with moving, which includes crowding and rising financial debt.

In the report, SES categories are based on Equifax Risk Scores, a type of credit score that ranges from 280 to 850 and approximates financial stability rather than income or wealth. Low-SES refers to a score less than 580 or no score, moderate-SES refers to a score between 580 and 649, middle-SES refers to a score between 650 and 749, and high-SES refers to a score at 750 or greater.

Crowding

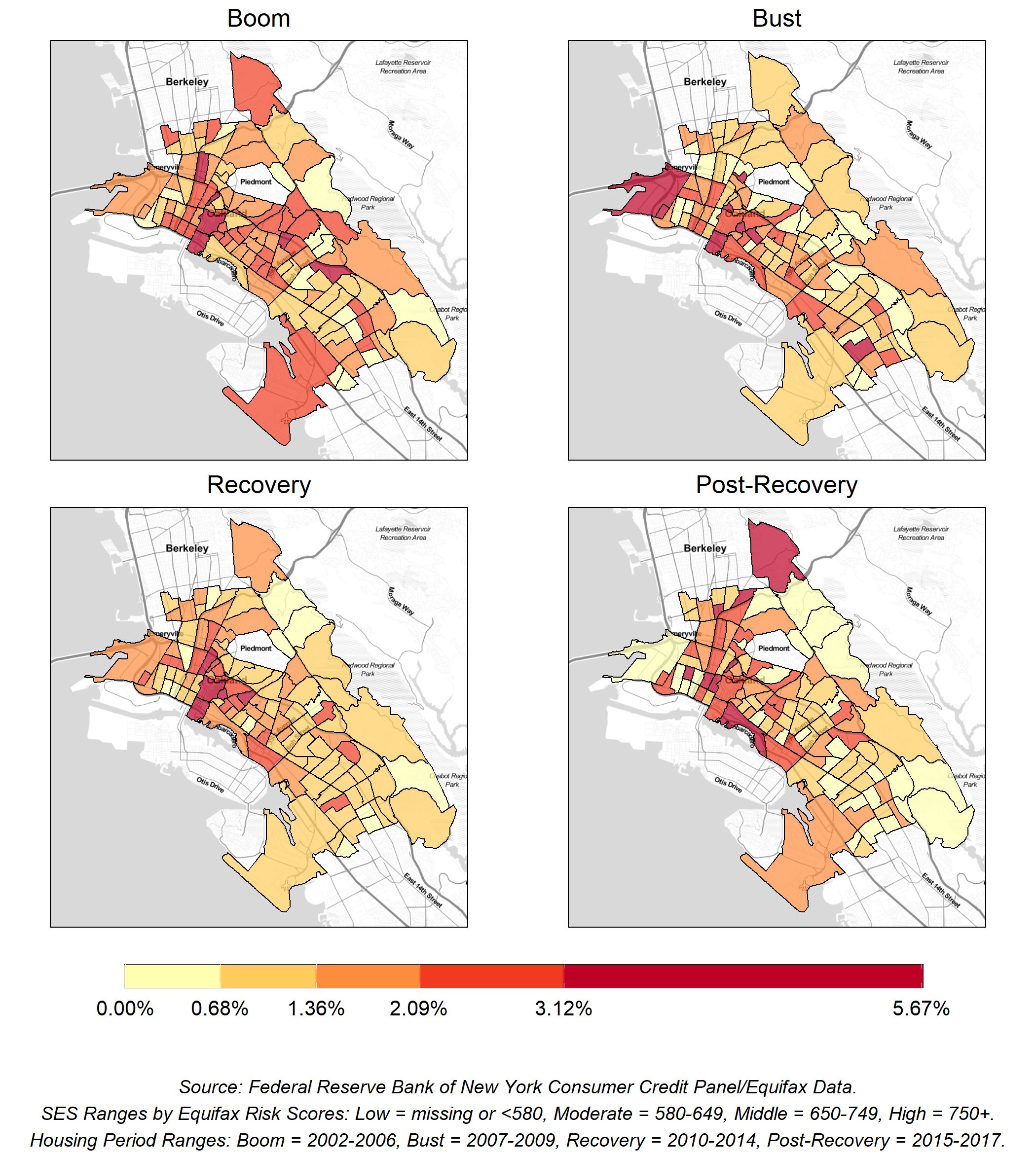

Across all housing periods1, Downtown Oakland had higher proportions of residents move and shift into crowded households compared with other neighborhoods in Oakland (Figure 1). We define shifts into crowded households by changes from low-density households with 1-2 adults to high-density households with at least 4 adults. During the Great Recession (“bust” period), this shift was also prevalent in West Oakland, and, during the periods after the Recession, the shift to high-density households was more widespread, occurring often among movers from North Oakland and parts of West Oakland.

Maps of the percent of low, moderate-, and middle-SES residents who move and shift from households with 1-2 adults to a household with 4+ adults in each period, based on where they are moving from.

Figure 1: Moves into households with more adults are more concentrated in Downtown Oakland and parts of North and West Oakland.

Neighborhoods in North and West Oakland which have experienced the most crowding are primarily Black and Black-Other.

Figure 2: Map of ethnoracial neighborhood categories.

Communities of color are particularly vulnerable to crowding. Figure 2 visualizes the corresponding ethnoracial categories3 for Oakland census tracts, based on their ethnoracial compositions in the year 2000, and demonstrates that the neighborhoods experiencing the most crowding shown in Figure 1 are disproportionately communities of color. Neighborhoods in West Oakland, where crowding was prevalent during the bust period, are primarily Black-Other. Only six census tracts were predominantly Black in the year 2000, and they are in West Oakland, North Oakland, and along highway 580 in East Oakland, which is where crowding was prevalent during the recovery and post-recovery periods.

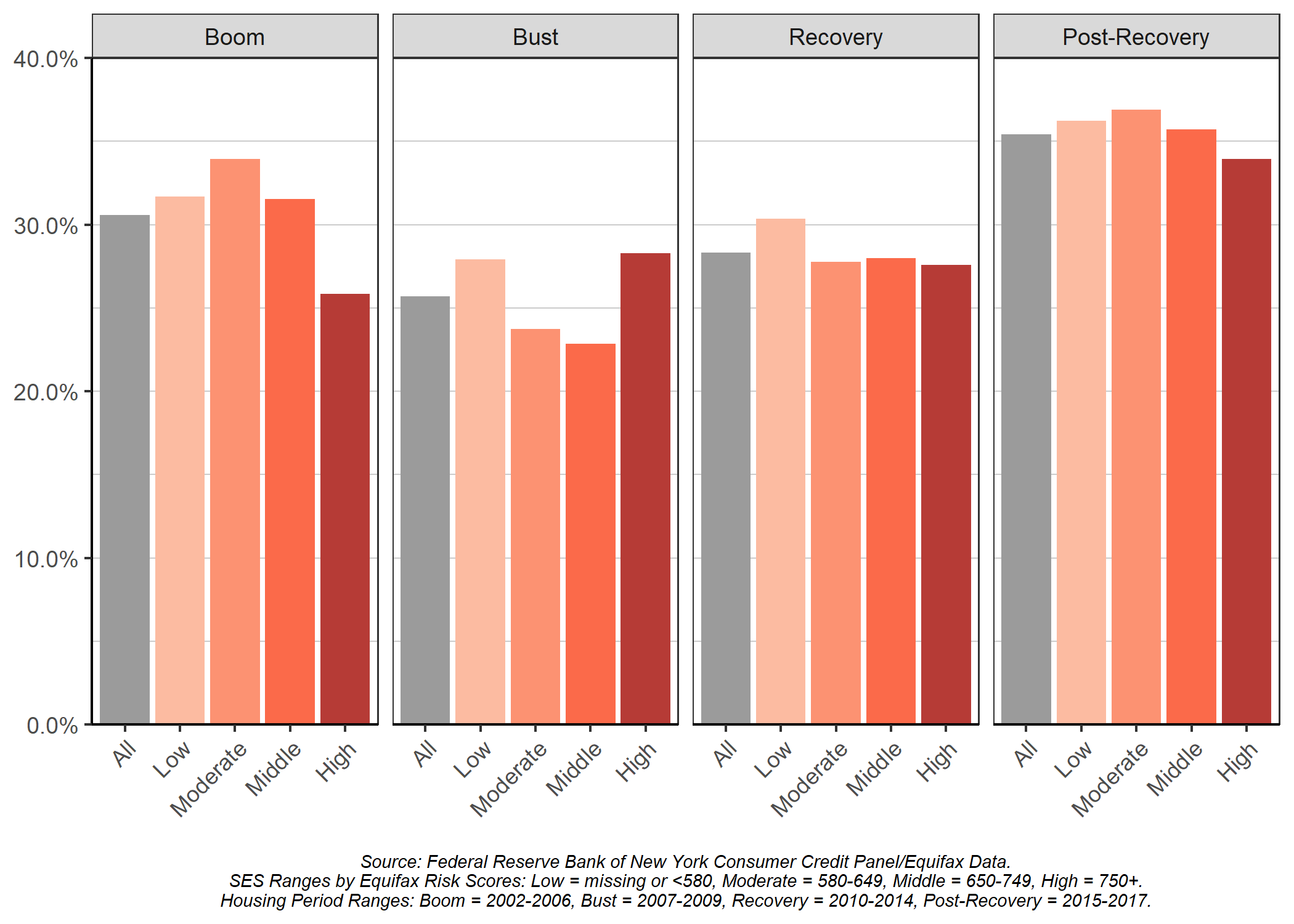

The shares of movers who shifted from low-density households to high-density households comprise a substantial proportion of movers and have increased across SES groups since the Great Recession. The largest increases took place after the housing market recovered in 2015 and characterized about 35 percent of low-density households who moved, perhaps reflecting the increasingly unaffordable housing market (Figure 3). High-SES movers, however, made this shift less than other SES groups, except during the housing bust.

The shift from low-density households to high-density households comprises a substantial portion of movers.

Figure 3: Percentage of all movers in Oakland who moved from households with 1-2 adults to a household with 4+ adults by SES and housing period.

Financial Instability

Although many residents move because of increased housing prices, others may stay in place and offset housing costs by forgoing payments on other household and living expenses. While moving to crowded households demonstrates one set of measures that reflects residential instability, the extent to which residents experience financial instability reflects another facet of residential instability that may eventually lead to forced or constrained moves.

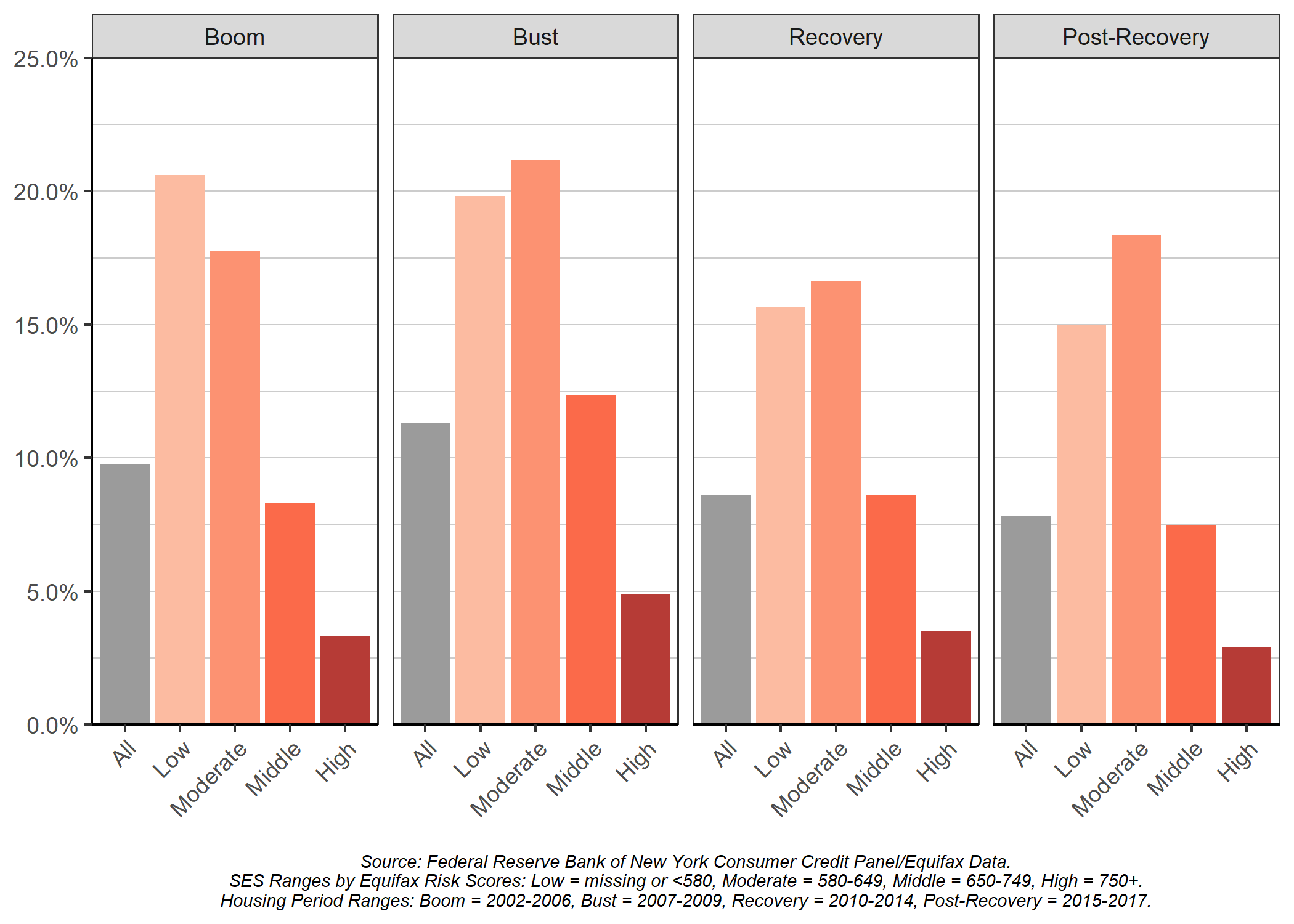

Our analysis shows that households became more financially insecure during the Great Recession and that moderate-SES residents did so after the housing market recovered. We analyzed the extent to which someone in a household became delinquent on any credit account over each year among households without any delinquencies. Figure 4 shows the percentage of households with new delinquencies, separated by SES (based on the beginning of each year) and housing period. The share of households with new delinquencies increased between the boom and bust periods among moderate-, middle-, and high-SES residents, while this share decreased among low-SES residents. The share of residents in these SES groups that shifted to low-SES status by the end of each year exhibited similar trends.

Moderate-SES residents experienced an increase in new delinquencies after the housing market recovered, while all other SES groups experienced decreases.

Figure 4: Percentage of Oakland residents in households with new delinquencies, by SES and housing period.

All SES groups, except for moderate-SES residents, experienced a decrease in the percentage of households with new delinquencies from the boom to post-recovery periods, which suggest that moderate-SES residents in Oakland may be experiencing more financial instability as affordable housing has become increasingly limited.

Crowding and Financial Instability in 2020

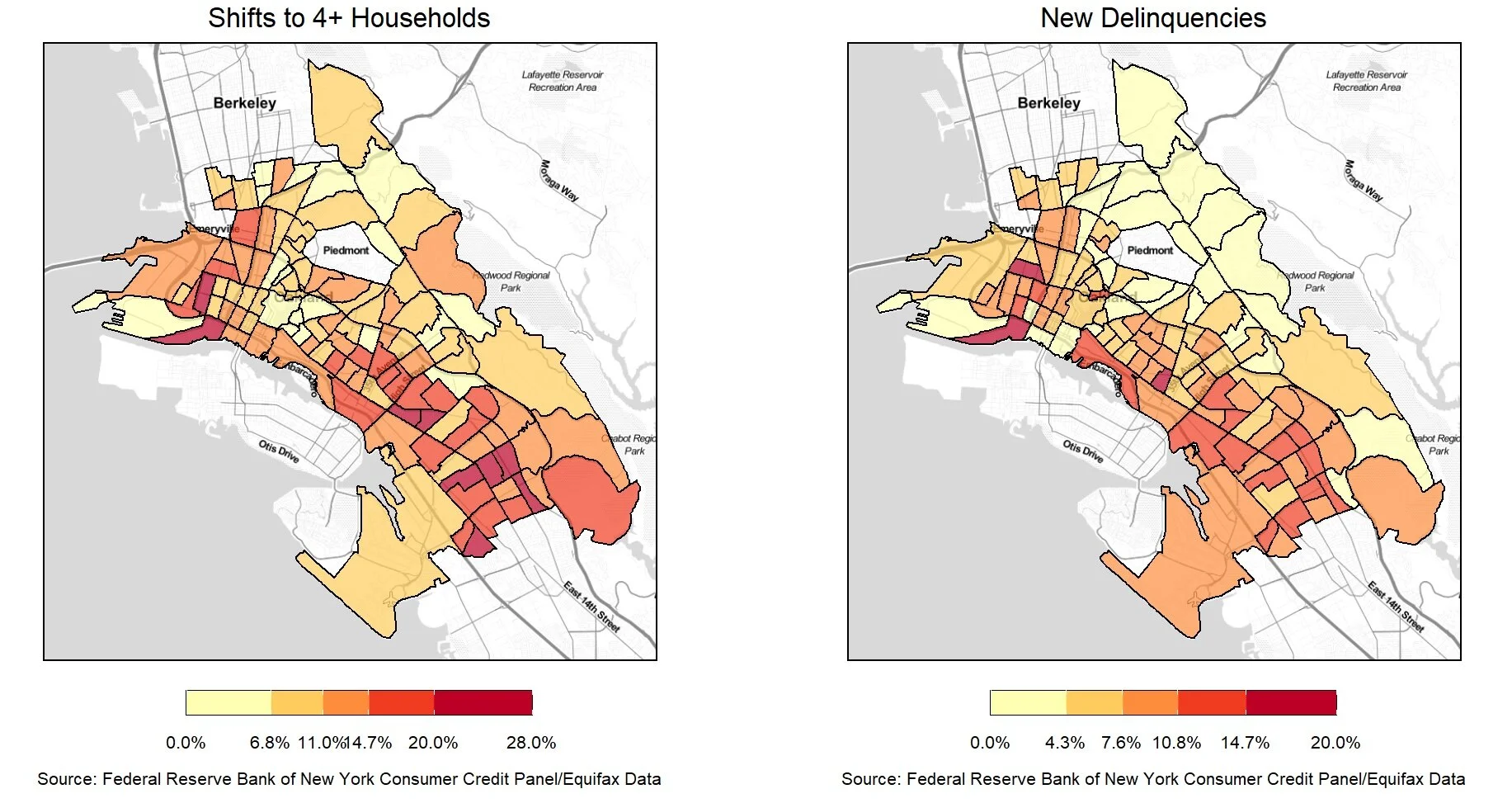

Crowding and financial instability have additional implications during the COVID-19 pandemic3. Recent data spanning 2020 suggest that moves into crowded households and financial instability are more widespread and more frequent compared to before the pandemic, which may reflect efforts to afford housing amidst the economic fallout from the pandemic. The maps in Figures 5 show an overlap between areas where more people are moving to crowded households and gaining new delinquencies, primarily West and East Oakland.

More residents have shifted into crowded households in more parts of Oakland since the pandemic started, and financial struggles are more widespread in historically socioeconomically disadvantaged areas.

Figure 5: a) Map of the percent of unique households that shifted into 4+ households from smaller ones during 2020, and b) Map of households that did not have a delinquency and became delinquent on a credit account.

These indicators for crowding and financial instability reflect an important tradeoff: people may be choosing more crowded conditions and increased financial instability to stay in the places they call home, to maintain their sense of community and social networks, to ensure school stability for their children, and to remain close to economic opportunity (among other factors), despite the various negative impacts of crowding and financial instability. Crowding and financial instability can create both short-term and long-term consequences, such as worse physical and mental health outcomes, behavioral outcomes, and educational attainment among children. Crowding also poses a public health risk during the pandemic, as crowded households increase the risk of contracting and spreading COVID-19. Further, it is important to continue monitoring crowding and financial instability, because they can be precursors to displacement and moving under severe constraints.

While crowding and financial instability have both increased across Oakland, especially among lower-SES residents during the COVID-19 pandemic, they nevertheless tend to be concentrated in certain regions (Deep East and West Oakland) that primarily fall in the Black-Other neighborhoods, and they appear to reflect distinct strategies that residents employ to avoid undergoing displacement. Policies should likewise be distinct and targeted to address the specific strategies that populations in different geographies are employing to avoid moving.

1 Boom (2002-2006), Bust (2007-2009), Recovery (2010-2014), Post-Recovery (2015-2017)

2 We define ethnoracial categories as including Multiethnic/Other (includes Predominantly Other Race and Multiethnic), White/White-Mixed (includes Predominantly White, Mixed White-Other Race, and Mixed Black-White), Black-Other (includes Mixed Black-Other Race), and Predominantly Black.

3 Bliss, Laura and Lorena Rios. 2020. “Tracing the Invisible Danger of Household Crowding.” Bloomberg.; Dougherty, Conor. 2020. “12 People in a 3-Bedroom House, Then the Virus Entered the Equation.” The New York Times.; Romero, Farida Jhabvala. 2020. “'What Am I Going to Do?' For Families Losing Wages, Bay Area Rents Are Now a Crisis.” KQED.

This is the second post in our series of Data Vignettes on Residential Instability in Oakland. Navigate to other posts in this series here.